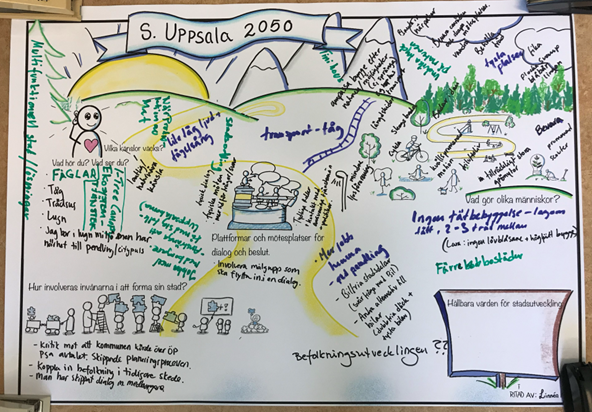

Envisioning urban futures is as much a social and political act as it is a spatial one. It involves negotiating how we want to live together, what values we prioritise, and whose voices are included in shaping those futures. In the case of south east Uppsala—where a large-scale development plan includes 21,500 new housing units, a train station, and tramlines—this act of collective imagining has become a site of contestation.

Whose vision shapes the city?

Insights from our workshop held on 28 March 2025 revealed not only sharp critiques of the Uppsala municipality’s plan but also a deeper tension around whose visions for the city are allowed to shape its future.

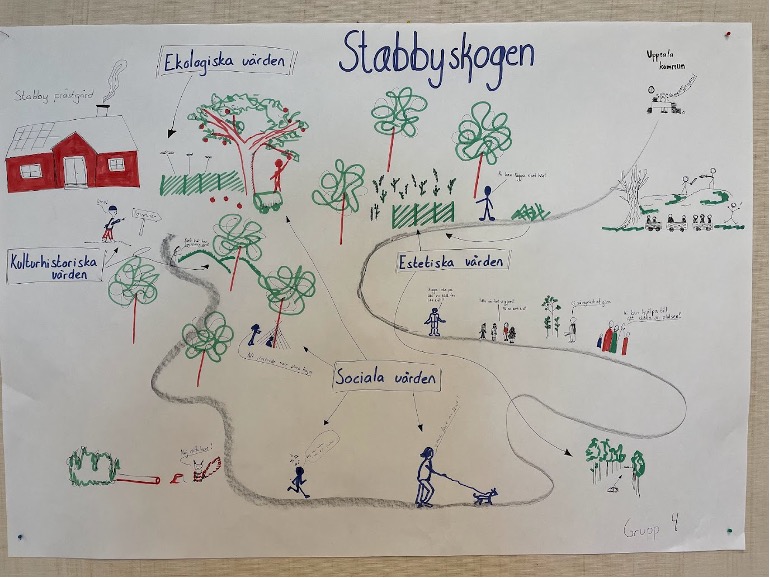

A central finding from the workshop discussion is the constrained capacity for collective urban envisioning. The pre-determined scope and parameters of the municipality’s proposal cast a long shadow over what was intended as a co-creative, open-ended exercise in urban imagination. The plan’s dominant framing seemed to set the agenda in a way that inhibited local stakeholders—residents, civil society actors, and others—from articulating alternative imaginaries of what the area could become in the future. While green spaces were generally appreciated during the discussion, they were often mentioned as “the icing on the cake” rather than central elements. As a result, discussions centred less on collaboratively creating desirable visions and more on shared concerns around the top-down nature of the formal planning process.

From critique to collective action

This sense of exclusion is echoed in the prevalence of critical narratives directed at the municipality. Many participants voiced concerns over the sheer magnitude of the proposed development and pointed to a lack of meaningful public consultation during the early planning phases. There is also a widespread perception that environmental concerns—such as the preservation of nearby natural areas like Lunsen and Årike Fyris—have not been given adequate weight. These criticisms reflect not only discontent with specific aspects of the plan but also broader concerns about transparency, public participation, and the democratic legitimacy of the planning process.

These critiques stood in stark contrast with the municipality’s assertion that citizen dialogue had been conducted thoroughly and that public opinions were incorporated into the planning process. During the workshop, a political representative emphasised the need to balance individual preferences with broader sustainability objectives—an approach that would inevitably involve difficult trade-offs. At the same time, there are clear calls for more innovative thinking, long-term planning and a landscape perspective that accounts for both local values and global challenges.

Re-imagining planning through co-creation

Interestingly, the workshop conversations also revealed strong place-based resistance among certain local residents, often manifesting as Not-In-My-Backyard (NIMBY) sentiments. Such responses speak to deep emotional and historical attachments to place. They highlight the underlying tensions between place-based attachments and the municipality’s overarching urban development ambitions. Resistance in this context is not necessarily about opposing urban development, but perhaps more about opposing a vision of development that feels imposed and disconnected from local identities and values.

Together, these findings suggest that creating opportunities for shared imagining among diverse stakeholder groups is key to making urban landscape management inclusive and co-creative. Such collaborative envisioning can complement formal planning frameworks by fostering spaces where community-driven ideas and narratives can meaningfully shape urban futures. Furthermore, the findings call for a shift in focus – from solely critiquing the structural limitations of formal planning to recognizing and embracing individual and collective agency to bring about change, even within those constraints.

The case of south east Uppsala is not just a technical matter of infrastructure, housing density or the encroachment on nature and green spaces. It is also a question of how to strike a balance between formal planning institutions and decisions made within representative democracy, and the potential that arises from innovative, co-creative approaches to imagining the collective future of multifunctional urban landscapes.

For more information, contact Thao Do (Uppsala University) in the Future imaginaries project.