Stabby woodland is located about 3 km west of Uppsala city center. The area consists of hills covered with mixed coniferous and deciduous trees and grasslands used for sheep grazing. Stabby woodland is a popular place for recreation for those living nearby. This year, the woodland became the stage for a student project in landscape architecture. Lara Tickle from LANDPATHs sub-project Urban Landscapes has been studying the project and tells us about how the students’ project promotes multifunctionality in urban woodlands.

Collaborative learning

In the LANDPATHS Urban Landscapes project we had the opportunity to follow and study the annual collaboration between the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU) and Uppsala municipality. A greenspace within the municipality is selected for students to design and revitalise as part of SLU’s Landscape Architecture course ‘Design through practice and management’ (‘Gestaltning genom Förvaltning’). In 2023, the students, who have learned various theories and methods (including multifunctionality in the management of urban greenspaces) were assigned a large area of the Stabby woodland to apply their ideas. Here the students could work creatively with new theories in a bottom-up fashion, and in a collaborative and co-learning environment with employees at the municipality. In this way, they ‘started with the doing’ and not, as is so often the case, with policies and plans.

The project is seen as an exchange of learning and skills between the university and municipality. It is facilitated by the creative setting, space for experimentation and its bottom-up working structure led by the students. Over the years that the course has been running, students have learned how to work practically. In exchange, the municipality has picked up new strategies and methods for understanding and managing urban greenspaces. Discussions are also in process about the potential to apply this cooperative model in other Swedish municipalities interested in involving more landscape architects in the management of their urban greenspaces.

Managing urban woodlands

Urban woodlands are structurally similar to forests and are hubs of rich biodiversity in urban areas. They are highly popular spaces for locals and used in various ways, especially for health, recreation and educational purposes. Children from nearby schools often play amongst the trees and greenery. Joggers regularly run along the paths, passing others who are enjoying a daily stroll that enriches their mental health in a diverse and natural environment. The students considered all of these stakeholders, together with the concern for biodiversity, which was included in several ways. For example, prior practice by the municipality consisted of removing forest debris. The students inspired the idea of working with these local materials. Dead wood and other materials are considered a primary indicator of biodiversity in a forest ecosystem that houses and sustains many species and has therefore become a popular new method for working with biodiversity in design.

As a results of the students’ work, municipal foresters now aim to leave materials such as logs, leaves, branches and other debris in neat formations wherever they have been working. Students used and arranged these materials to make benches, play areas, hedges to emphasise a space or even weave local plants into a labyrinth for children to play in. Also, people from the municipality were encouraged to use their skills in other ways. For instance, one person who was especially skilled with a chainsaw made wooden sculptures to highlight features and species in an area.

Picture: Lara Tickle

“Doing things multifunctionally” in urban woodlands

During the collaborative work, we could observe how people apply principles of multifunctionality and nature-based thinking, or as one lecturer at the university says, “nature-based doing”. Students often strived to highlight or bring out certain features out of the landscape they were working in. For example, they scouted out and observed the area prior to the week in which they would be implementing their designs. After they had drawn up the plans that were presented to the municipality, one idea was selected as the main guide. Nevertheless, the work still allowed for a lot of freedom to try out other ideas on site. The co-creation process opened up new spaces and paths through the forest and refreshed old spaces. The students cleared overgrown paths and used woodchips from local roads to make easy walking or jogging paths. Historical sites were also enhanced visually in the landscape by clearing overgrown vegetation and placing benches close by. Furthermore, hedges were made from leaves and twigs to form habitats for insects.

Evaluating and reflecting on the process

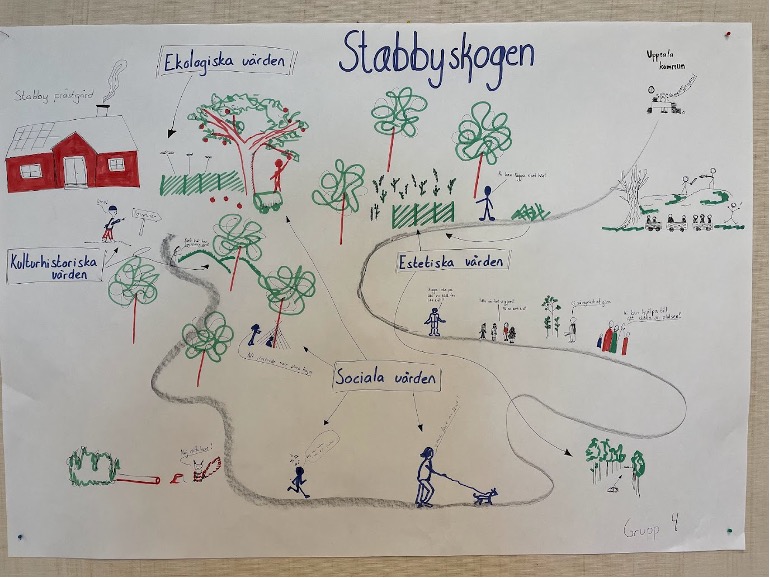

After an intense week of work in Stabby woodland the students presented their work to the public as part of a guided tour during an opening event. Each group presented the work they had done, as well the intentions behind their ideas and designs, who they were aimed at, and the qualities they tried to highlight and support in the woodland. In addition, department heads and other senior officials from the municipality emphasized during their presentation that the project was a successful cooperation between the two institutions.

In focus group meetings arranged by the LANDPATHS urban landscapes project, students mentioned that there are very many functions that need to be fulfilled by urban greenspaces, especially compared to other urban areas. They understand the challenges and difficulties that they can be faced with in their work, although this project still had a very positive atmosphere surrounding it. Engagement by local users of the woodland was high, and social values were very much highlighted in the woodland. Also, the importance of keeping areas like this one accessible to people in the city was raised, as such environments fill lots of important roles. Despite this, urban greenspaces face a lot of pressure.

Foto: Lara Tickle

At the end of the annual collaboration the students reflected on these points and more through rich picture exercises and dialogue with LANDPATHS researchers. They emphasized that greenspaces are essential, yet while they continue to decline they must also fill a growing number of functions that are sometimes conflicting.